The most dangerous position to hold in Great Britain was being an active ruler. Opposition groups, including other rulers, were a constant threat to a king or queen’s life. Elizabeth I was more vulnerable by virtue of her being a ruling woman. The threat was heightened by the religious tensions between Protestants and Catholics in England. Before Elizabeth I, England had a Catholic queen, Mary I of England, and now Elizabeth I, a Protestant queen, faced the task of controlling religious riots. Elizabeth had members of court that used advanced techniques of secret intelligence to ensure her safety and control potential plots of treason.

One remarkable secret intelligence agent of Elizabeth I was Sir Francis Walsingham, the man responsible for taking down Mary, Queen of Scots. His efforts to expose Mary, Queen of Scots was less of a matter of being devoted to Elizabeth I, but more of a devotion to Protestantism.

Before entering the world of espionage, Sir Francis Walsingham served as England’s Ambassador to France. He arrived in France on January 1, 1571 in Boulougne and, soon after, made his way to Paris where he would serve as the ambassador for 10 years. During his time in Paris, one of the bloodiest tragedies would occur and influence his quest to take down Mary, Queen of Scots and any other Catholic conspirators.

In 1572, Walsingham witnessed the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre in Paris, which sought to slaughter prominent Protestant Huguenots. The first wave of assassinations came after the wedding of Margaret and Henry III of Navarre. This lasted several weeks and left the power of the Protestant Huguenots in critical condition. Not only was this traumatic for Walsingham, but this served as a warning to England. A Catholic rebellion, such as the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre, could crumble England’s Protestant monarchy. The rebels would have a goal and figure to fight for to give their battle a meaningful purpose, which has historically proven to be a key in leading a successful battle. During this time, Mary, Queen of Scots was imprisoned in England, and a Catholic triumph could easily establish their new power by freeing Mary and crowning her as queen. Walsingham’s realization of how dangerous it was to keep Mary alive through him into an urgent frenzy to take her down.

Records show Sir Francis Walsingham’s plea of urgency to his majesty, Queen Elizabeth I:

“ … the malady in time will grow incurable, and the hidden sparks of treason that now lie covered (will no doubt it) break out into an unquenchable fire. For the love of God Madam, the not the cure of your diseased estate hang in deliberation any longer.”

After expanding his secret intelligence network during his secretaryship, Walsingham received encouraging support following the marriage of his daughter to Sir Philip Sidney. Walsingham’s new son-in-law was as ambitious as he was to secure a Protestant monarchy. In 1583, Walsingham’s pessimism had a solid cause after he uncovered the Throckmorton Plot, which was a plan to free Mary, Queen of Scots and place her on the throne of England. A year later in 1584, the Bond of Association, created by Sir Francis Walsingham and William Cecil, was passed by Parliament and signed. In the case of an assassination or attempted assassination on Queen Elizabeth I, the participants of this document pledged to vindicate all parties directly or indirectly involved in the treasonous act. And, certainly, the Queen of Scots was the main person this applied to.

The Babington Plot of 1586 was the scheme that sealed the deal for Walsingham’s triumph over Mary, Queen of Scots. By this time, the Scottish queen had been under house arrest for over 15 years, and Queen Elizabeth’s refusal to execute her ignited Walsingham’s impatience with the situation. Out of all the plots for a Catholic uprising and assassination on Elizabeth I, the Babington Plot remains the most controversial. The scheme itself was not unusual, but the details surrounding Sir Francis Walsingham’s involvement has caused controversy among historians. The plot was set up by Walsingham, and, essentially, trapped her. Walsingham began to orchestrate the plot by transferring Mary from her Tutbury home prison to Chartley. At Chartley, Mary would lose the little freedom she had and become isolated. Perhaps, Walsingham hoped isolation would hatch vengeful emotions and an extreme urge to escape by any means; thus, leading her into an agreement with the plot Walsingham would plant.

After Mary was settled in her new place of imprisonment, Walsingham hired Thomas Phileppes, a highly regarded cryptographer who spoke French, Italian, Latin, and German, to decode messages between Mary and co-conspirators. Phileppes constructed a route that could secretly conduct letters to the imprisoned queen. Next, Walsingham needed someone to act as a double-agent.

Gilbert Gifford was chosen as the double agent, most likely due to his ties to the Catholic church. Gifford was an excellent choice since Mary would not suspect a Catholic sympathizer would be baiting her.

The final arrangement included a plan of concealing the letters, opening/closing the seals, and receiving the approval of Mary’s prison superintendent. Arthur Gregory and Thomas Rogers were hired to reseal Mary and her co-conspirators’ correspondence that Walsingham would be reviewing and Thomas Phileppes would decode. Then, the beer delivery man, only known as “The Honest Man,” was easily lured into the scheme. “The Honest Man” delivered beer to Mary every week and would conceal the letter. The letters were hidden in the beer barrel’s cork and kept dry through a waterproof tube Phileppes designed.

The trap was set, and, on January 12, 1586, a test letter was sent from Chateauneuf, the French Ambassador to England. Once Chateauneuf confirmed the mail route Walsingham constructed was safe, Walsingham began collecting his evidence.

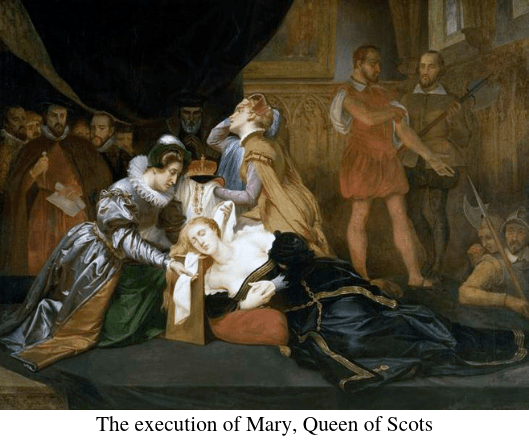

The title “Babington Plot” came from the culprit who participated in the letters that secured Mary’s fatal charges. One of Mary’s agents recommended that she should reach out to Babington, as he was a young, Catholic enthusiast who wanted to rescue the Scottish queen. The letters between Babington and Mary were incriminating and violated the Bond of Association. Walsingham’s plan was successful, and, by September 18, 1586, Babington and co-conspirators were disemboweled then hanged to death. As for Mary, Queen of Scots’ sentence, Elizabeth I never approved or signed her death warrant. Walsingham went to the Council for Mary’s execution approval, and, so, she was beheaded on February 8, 1587.

On April 24, 1558, Mary, Queen of Scots and Francis II of Valois, the Dauphin of France, wedded at Notre Dame Cathedral. This was Mary’s only favorable and politically savvy marriage. Francis, the son of Henry II and Catherine de’Medici, was next in line to the French throne, which put Mary in a powerful position to reign as a queen in two countries, and it wouldn’t be long until this happened. Francis and Mary became the King and Queen of France in 1559, but the glory of reigning over two countries would be short-lived. The death of Francis II of France on December 5, 1560, set the events of Mary’s doom into action. Mary became a childless widow after Francis’ death. Since a queen’s security in the French court depended on producing heirs, and Mary did not do so, her time in France came to an end. With modern intelligence, we understand Mary’s childlessness should not be viewed as a “failure” to reproduce or understood as entirely her fault. In fact, Francis II had several illness including

On April 24, 1558, Mary, Queen of Scots and Francis II of Valois, the Dauphin of France, wedded at Notre Dame Cathedral. This was Mary’s only favorable and politically savvy marriage. Francis, the son of Henry II and Catherine de’Medici, was next in line to the French throne, which put Mary in a powerful position to reign as a queen in two countries, and it wouldn’t be long until this happened. Francis and Mary became the King and Queen of France in 1559, but the glory of reigning over two countries would be short-lived. The death of Francis II of France on December 5, 1560, set the events of Mary’s doom into action. Mary became a childless widow after Francis’ death. Since a queen’s security in the French court depended on producing heirs, and Mary did not do so, her time in France came to an end. With modern intelligence, we understand Mary’s childlessness should not be viewed as a “failure” to reproduce or understood as entirely her fault. In fact, Francis II had several illness including  Mary’s return to Scotland wasn’t necessarily the mishap; it was her poor decisions and judgment she made upon her return. Having called herself “Marie,” the French variation of her birth name, Mary returned to her native land as more French than Scottish. She entered Scotland as a Catholic queen and lacked the understanding of Scotland’s political and religious climate that caused a split between Catholics and Protestants.

Mary’s return to Scotland wasn’t necessarily the mishap; it was her poor decisions and judgment she made upon her return. Having called herself “Marie,” the French variation of her birth name, Mary returned to her native land as more French than Scottish. She entered Scotland as a Catholic queen and lacked the understanding of Scotland’s political and religious climate that caused a split between Catholics and Protestants. Mary and Lord Darnley shared the Stuart last name before their marriage since they were cousins. After meeting her cousin, her youthful passions were aroused as Mary described him as “the lustiest and best proportioned long man that she had seen.” If only she would have heeded to the warning from her cousin, Elizabeth I of England, about the poor choice to wed Lord Darnley, but Mary was determined to marry her “lusty man.” Almost instantly after exchanging their vows, Lord Darnley became notorious for his outrageous behavior. Mary’s only smart decision concerning her second husband was refusing to concede to the Crown Matrimonial – the right to co-reign with one’s spouse. This caused Darnley’s wrath of not having power to boil over. His next plan to ensure becoming king was to avoid fathering an heir. Darnley thought an heir would push him further away from ascending to the throne. However, Mary’s passion for lusty Lord Darnley succeeded in producing a son, James VI, the future King of Scotland and King of England and Ireland (under the name of James I).

Mary and Lord Darnley shared the Stuart last name before their marriage since they were cousins. After meeting her cousin, her youthful passions were aroused as Mary described him as “the lustiest and best proportioned long man that she had seen.” If only she would have heeded to the warning from her cousin, Elizabeth I of England, about the poor choice to wed Lord Darnley, but Mary was determined to marry her “lusty man.” Almost instantly after exchanging their vows, Lord Darnley became notorious for his outrageous behavior. Mary’s only smart decision concerning her second husband was refusing to concede to the Crown Matrimonial – the right to co-reign with one’s spouse. This caused Darnley’s wrath of not having power to boil over. His next plan to ensure becoming king was to avoid fathering an heir. Darnley thought an heir would push him further away from ascending to the throne. However, Mary’s passion for lusty Lord Darnley succeeded in producing a son, James VI, the future King of Scotland and King of England and Ireland (under the name of James I).

Not only was James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell, the man accused of killing Mary’s second husband, he was also the man who kidnapped her. Yet, Mary ignored the controversy surrounding Bothwell and the two were married on May 15, 1567, at the Chapel of Holyrood Palace. By June 15, 1567, the marriage ignited a battle, known as the Battle of Carberry Hill, between the Hamiltons (the Queen’s supporters) and the Confederate Lords (rebels). The Confederate Lords sought revenge for the murder of Mary’s second husband and showcased a banner illustrating Lord Darnley’s murder scene.

Not only was James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell, the man accused of killing Mary’s second husband, he was also the man who kidnapped her. Yet, Mary ignored the controversy surrounding Bothwell and the two were married on May 15, 1567, at the Chapel of Holyrood Palace. By June 15, 1567, the marriage ignited a battle, known as the Battle of Carberry Hill, between the Hamiltons (the Queen’s supporters) and the Confederate Lords (rebels). The Confederate Lords sought revenge for the murder of Mary’s second husband and showcased a banner illustrating Lord Darnley’s murder scene.